Ant Farm: 1968 – 1978, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive

These reflections were published as a short exhibition review in Bomb Magazine. A copy of the published article can be found here, or this post can be cited as: Buckner, Clark. “Ant Farm, 1968 – 1974, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive.” Resonator. Web. Day, month, year the post was accessed.

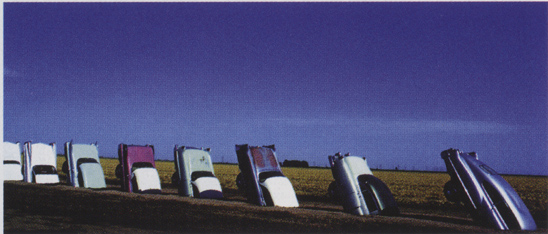

Ant Farm (Chip Lord, Hudson Marquez, and Doug Michaels), “Cadillac Ranch,” 1974, site-specific installation, Amarillo, TX. Courtesy of the University of California Press.

In 1972, the art collective, Ant Farm, constructed a time capsule by filling a refrigerator with such everyday cultural artifacts as candy bars, magazines, fake eyelashes, and a television. They called it an “open door to the American dream,” but, when they opened the fridge in 1984, its contents were rotten and corroded. Fascinated by both the power of mass-produced images and the transience of modern life, Ant Farm created models for nomadic living (most of its members were trained as architects) and staged confrontations with junk culture, which both reflected the seductions of the modern world and challenged their pretenses to lasting value.

Apart from the inflatable dwelling “Ice-9,” which sat like a landed blimp at its center, the Ant Farm exhibition at the Berkeley Art Museum appropriately contained very few recognizable art objects. Instead, notebooks, plans for projects, magazine articles, news clippings, video reels, record albums, posters, and photographs provided traces of works. Using a range of media, including video, installation, and environmental activism, the collective directed their preoccupations primarily to performative or conceptual projects. And, among other things, they were particularly fascinated by the American automobile, which they took to embody a utopian, nomadic ideal. If we all climbed into our cars with a couple of friends, they noted, “Every American would be accommodated and there would be room to spare in the back seat.” This love of cars found its highest expression in the well-known installation Cadillac Ranch, comprised of 10 Cadillac sedans half-buried hood-first in a row in Amarillo, Texas. The piece presents a history of the tail-fin from 1949 to 1964, constituting a tribute to the Cadillac as a symbol of luxury and accomplishment, while also staging the forced obsolescence implicit in modern design by driving the cars literally into their graves.

The collective also repeatedly returned to the utopian promises of television, both exploring its potential for the construction of novel social environments and critically dissecting its almost mythical power. Their experiments in future-living put them in close contact and critical dialogue with the American dream.