“100 Artists See God,” at the Contemporary Jewish Museum

From the fundamentalism of both Islamic and Christian varieties to the amorphous affirmation of New Age mysticism, religion has returned to the modern world with a vengeance. So, when I saw the announcement for the exhibition at The Contemporary Jewish Museum, “100 Artists See God,” I was skeptical, anticipating images of the video artist Bill Viola dissolving into sheets of baptismal rain. Despite the language of the curators that often seemed to treat the works presented as diverse expressions of faith, however, the show was rich with art that approached religion with suspicion, attempting to see God, through mankind’s fear and narcissism, for what “He,” too often, turns out to be.

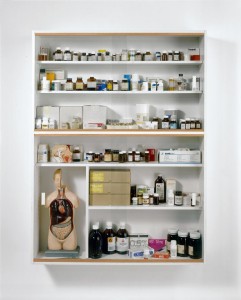

Some of this work featured fetishes that people now often elevate to sources of salvation. Damien Hirst reconstructed a cabinet full of medical supplies, pointing to the contemporary psycho-pharmacology of the soul and the desperation with which we sometimes cling to science in the face of death. Christopher Williams offered a carefully crafted photograph of dishes in the dishwasher, evoking the promise that commodities might ultimately redeem us from the toils of labor. Other works critically explored the sources of religious sentiment. Photographs by Richard Prince and Andreas Gursky presented scenes of crowds from pop-culture love fests. Raymond Pettibon and Liz Larner each approached the divine in terms of a child’s often ambivalent feelings for its mother. And, while the show also had its kitsch elements with rays of light piercing through clouds, even some of the more pious pieces were subtle and compelling.

My favorite work from the show included Tony Oursler’s video projection of “the face of God” onto a styrofoam ball with scraggly white hair. The video was both terrifying and absurd, presenting God, pontificating about his divinity and the universe, as the shadow of some self-important, alcoholic step-father. Jen Liu’s techno-pop music-video declared architecture to be “the real battleground of the spirit,” and staged a videogame-like confrontation between Mies van der Rohe, Buckminster Fuller and Adolf Loos, with cities violently destroyed and reconstructed in rapid succession. And Paul Pfeiffer’s video, “Fragment of a Crucifixion,” presented a black basketball player isolated on the court repeating expressions of terror and rage, with a violence and physical intensity that both drew upon the history of religious art and spoke to contemporary social and political conflicts.