The Experimental Conditions of Exhibition Practice: On the Curator’s Role in Contemporary Art

This essay was published in Art Journal, Volume 68, No. 3. Fall. Download a pdf of the original here, or cite this post as: Buckner, Clark. “The Experimental Conditions of Exhibition Practice.” www.clarkbuckner.com. Web. Day, Month, Year article as accessed.

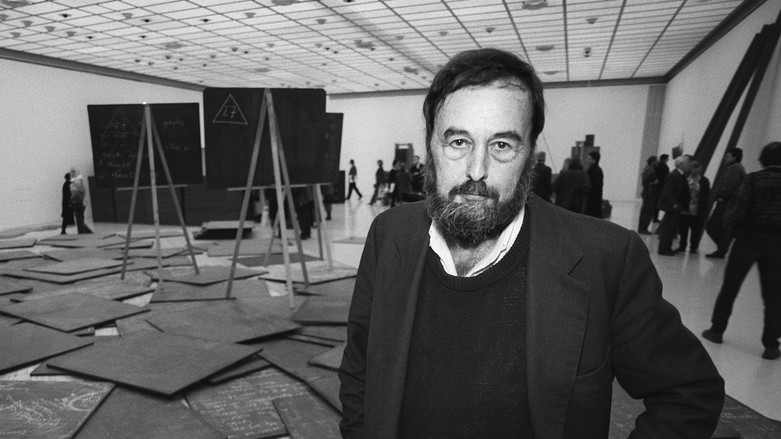

In recent decades curators not only have achieved a new degree of prominence in the art world, they have come to play a decidedly new role, inspiring the legendary Swiss curator Harald Szeemann—one of the first of this new breed—to prefer the title “exhibition-maker” as a way to mark the distinction between his work and that of his predecessors. In the process, curators have come to embody an amalgam of decisive shifts and novel problematics in contemporary art. As evidence of this changing role and its growing importance, since the mid- 1990s art schools and colleges have generated a profusion of new MA programs in curatorial practice, programs whose curricula combine art history, visual studies, and critical theory in varying degrees, frequently with an emphasis on contemporary, “post- conceptual” art forms, public engagement, and creative collaboration.1 Such programs respond to a growing interest in and professional market for contemporary art curating. Yet their positions remain precarious vis-à-vis the larger art market and its institutions, as do those of the growing numbers of professional curators they graduate. Not surprisingly, in recent years a spate of articles and books has been published to serve the needs of these new programs and to address the complexities inherent in curating now.

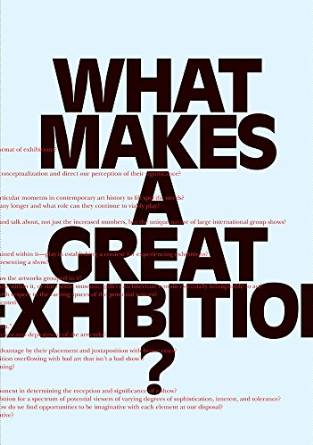

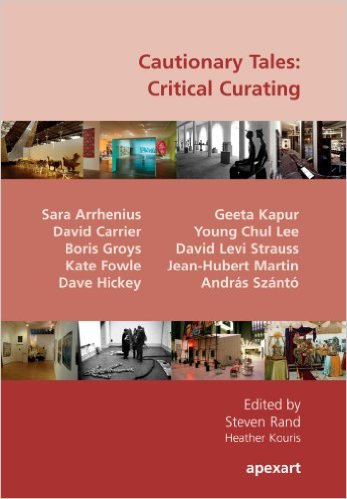

Of the three recent essay collections under review here, What Makes a Great Exhibition?, edited by the Philadelphia-based curator Paula Marincola (and hereafter noted as WMGE), provides the most conventional account of curatorial practice, including a lead essay by Robert Storr on a curator’s responsibilities and the potential pitfalls associated with different types of exhibitions, along with an article by Ingrid Schaffner on the use of wall text. For some- one particularly interested in the curator’s new role, its historical development, and the problems and possibilities it presents, I would more strongly recommend the two other collections, which focus exclusively on these questions: Cautionary Tales: Critical Curating, edited by Steven Rand, the director of Apex Art, and the Athens-based curator Heather Kouris (hereafter noted as CT), and Curating Subjects, edited by the London-based curator and writer Paul O’Neill (noted as CS). Of these two, O’Neill’s collection is simply more extensive and so ultimately the better. Nevertheless, all three collections include excellent essays (including one published in both Curating Subjects and What Makes a Great Exhibition?) that speak to one another and contribute to answering a shared set of questions: Who is this new curator? What does she do? What needs does she fill? What contradictions does her work involve? And what does the importance of her new role reveal about art today?

Working to address the pragmatic concerns introduced above, Storr in his essay “Show and Tell” establishes the connection between exhibition-making as a practical endeavor and as a process of meaning-making, through a series of analogies between spatial and textual practices. He writes, “Space is the medium in which ideas are visually phrased. Installation is both presentation and commentary, documentation and interpretation. Galleries are paragraphs, the walls and formal subdivisions of the floors are sentences, clusters of works are clauses, and individual works, in varying degrees, operate as nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs, and often more than one of these functions according to their context” (WMGE, 23).

Curators mediate among artists, institutions, and audiences as organizers and installers of exhibitions. Because this mediation is both practical and interpretive, the curator’s work is simultaneously entrepreneurial, critical, and creative. In order to clarify the diverse aspects of exhibition practice and account for their complication, Storr and others consistently appeal to metaphors. Storr himself compares the curator to an artist, a film director, a literary editor, and an entrepreneur. The curator Okwui Enwezor echoes the central analogy in Storr’s statement above by comparing the curator to a writer. The photography critic and poet David Levi Strauss introduces a seemingly endless list of possible analogies to the curator, including advocate, animator, bureaucrat, catalyst, cartographer, and diplomat.

While overlapping skills of critical judgment, narrative-generating creativity, and administrative and social acumen have long been implicit in curatorial practice, changes in the art world over the last forty years have brought these diverse aspects of the curator’s work to the fore, intensified them, exaggerated the contradictions they entail, and ultimately changed them from dynam- ics implicit in the practice to active features of exhibitions that frequently transcend and potentially upstage the works they frame. In this vein, Jens Hoffmann, for example, not only compares curating to filmmaking, but appeals specifically to the French New Wave director François Truffaut to claim for the curator the mantle of auteur.

To many, of course, such claims to curatorial authorship seem hyperbolic. The endless analogies between curating and other practices seem overstated and fatuous—as if curating were some sort of meta-expertise. Indeed, the figure of the curator as a globe- trotting international power-broker often seems pretentious—but no more so than the contemporary international art star—and the more historically self-conscious essays in these three collections nicely explain the development of exhibition-making into a self-consciously generative practice as an unavoidable consequence of changes in art since the 1960s, changes that have resulted in conditions in which the roles of artists, curators, and others remain relatively under- determined. In this light, rather than as a new version of the heroic genius, rivaling an equally outmoded image of the artist, the contemporary curator is best understood as a more modest figure that has emerged from the shadows of twentieth-century exhibition practices; he or she has assumed a position not on firm ground but amid the uncertain- ties that, in recent decades, have resulted from the destabilization of artworld conventions and institutions.

As in so much else concerning contemporary art, however, the question remains whether the experimental curatorial practices engendered by these uncertain conditions in fact carry critical force. Do they broaden the field aesthetically or conceptually? Or do claims to experimentation, process, and complexity serve rather to disavow the subordination of both artists’ and curators’ work to instrumental ends in a novel service economy that not only competes with but in fact resembles the consumer spectacles of mass entertainment. In this vein, while tracing the origins of contemporary curatorial practice to earlier avant-garde strategies of the 1960s, much of this discussion risks obscuring the concrete realities of contemporary exhibition practices and the assimilation of these strategies in the institutions they purportedly challenged.

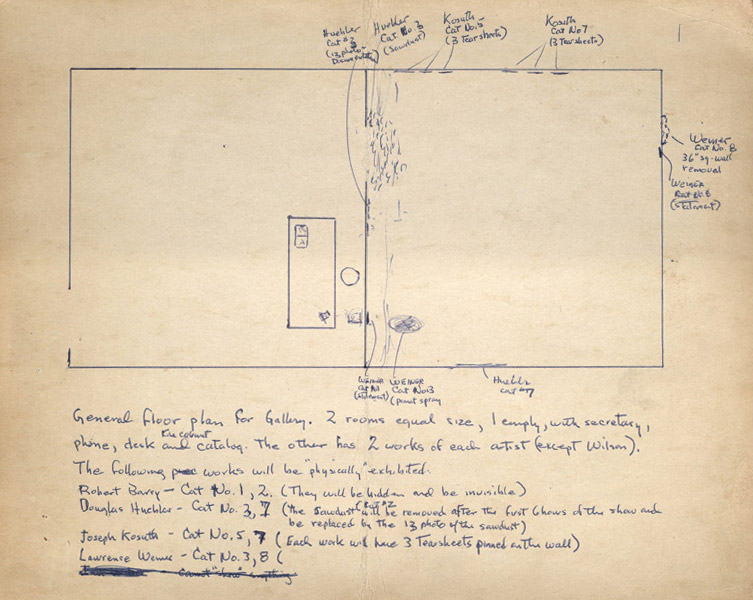

In “Creating Shows: Some Notes on Exhibition Aesthetics at the End of the Sixties” (CS) the Italian curator Irene Calderoni locates the advent of the curator’s new role in a series of exhibitions from the late 1960s, including: Teatro delle Mostre (Galleria La Tartaruga, Rome, 1968), Nine at Leo Castelli (Castelli Warehouse, New York, 1968), January 5–31 (Seth Siegelaub, New York, 1969), Op Losse Schroeven/Situaties en Cryptostructuren (Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, 1969), Anti-Illusion: Procedures/ Materials (Whitney Museum, New York, 1969), Spaces (Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1969), 557,087 (Seattle Art Museum, 1969), and Information (MoMA, 1970). These landmark shows, Calderoni contends, not only functioned “as the vehicles of the movements they rendered visible, but also as works in themselves, which managed to express a level of meaning and experimenta- tion of their own” (CS, 65). She explains the curatorial strategies at work in these exhibitions as consequences of the efforts of postwar artists, under the force of modernism’s critical self-consciousness, to engage the conditions of their works’ display as the substance of their concerns. Diverse site- specific and process-oriented art practices collapsed the distinctions between an artwork’s creation and exhibition, as artists abandoned their studios and began to work directly in galleries, museums, and other locales. The exhibition space and its conventions were brought to the fore as the very material of the work and were subjected to artists’ transformative interventions.

In her condensed history of London’s Whitechapel Gallery, “Temple/White Cube/ Laboratory,” the former Tate Modern curator and current Whitechapel director Iwona Blazwick traces this engagement with the space of the gallery to Minimal art, describing Donald Judd’s use of the floor not merely as the physical support for his work but as the site of an event—“a new field of making and experience” (CS, 128). Drawing on such shifts to a newly activated, horizontal, and phenomenological orientation, Blazwick argues, artists like Helio Oiticica engaged the gallery as a social space to be physically inhabited and explored. In “Curatorial Moments and Discursive Turns,” the Irish artist and writer Mick Wilson correlates the thematizing of the gallery’s infrastructure with the turn to discourse in art practice “from Robert Barry’s ontological investigations into the limits of the art object to Hans Haacke’s social surveys, from Mary Kelly’s psychoanalytic meditation and appropriation of the exhibition as system . . . to Tino Sehgal’s theatrical gamesmanship” (CS, 206).

Donald Judd at David Zwirmer gallery, installation view, photos courtesy of David Zwirmer gallery and the Judd Foundation

More on point, perhaps, are the models provided by artists who challenged the constraints of the studio-gallery-museum system by themselves working as curators. The former director of the curatorial- practice program at California College of the Arts, Kate Fowle, recounts (in CT) the early 1950s efforts of Jean Follett, Allan Kaprow, and George Segal to form the Hansa Gallery in New York’s Greenwich Village, challenging the conventional, hierarchi cal model of exhibition-making by having shows curated by artist committees—at the time, an unorthodox and even revolutionary practice. Concurrently, the Independent Group formed around London’s Institute for Contemporary Art to provide a forum for public debate through lectures, dialogues, and exhibitions in an anti-elitist, anti-academic vein; the group considered artworks in a broad cultural context that also included movies, advertising, fashion, and product design.

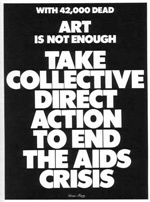

Other collectives, largely emerging in the 1980s, worked in a more overtly political way to expose and explore the social implications of representational structures both in and beyond the art world. In this vein, the artist and former Group Material member Julie Ault recounts, “Exhibitions are crucial junctions within which art and arti- facts are made accessible to audiences, and particular narratives, histories, and ideas are activated. Furthermore, every mode of dis- play establishes relationships between artist, art, institution, and audience and generates routines and rituals for looking. It is precisely because of the power that exhibitions have in assigning or opening up meanings, in creating contexts and situating viewers, that standardized exhibition methods and formats as well as display conventions need to be critically rethought and potentially subverted” (CS, 32).

Of course, the overtly political projects by collectives like Group Material, Colab, and Gran Fury should be distinguished from the more self-reflective aesthetic projects of the late 1960s, despite their relative populism and anti-establishment motivations. If we want to avoid over-hastily presuming that contemporary exhibition practices are either politically progressive or even, strictly speaking, aesthetic, the concrete continuing influence of each would require more careful consideration than I found in any of the collections here under review. Nevertheless, in different ways, both projects clearly contributed to disrupting the purported neutrality of the gallery’s white cube and, at least implicitly, presented the work of curators as potentially creative.

While challenging the aesthetic and institutional framing of art practice, the transformations of the 1950s and 1960s also changed the practical relationship between artist and curator—and, as a result, the relationship between curator and institutions. Curators no longer primarily selected works to exhibit, but rather chose artists from whom to commission projects. No longer simply mediating the presentation of existing artworks, curators came to play an integral role in their realization—replacing a model of distanced connoisseurship with one of almost militant advocacy. This involvement compromised the transparency and neutrality that previously characterized curators’ claims to critical authority, and brought them into more ambivalent and frequently antagonistic relationships with the institutions where they worked. Since the early 1970s, these shifts have resulted in the emergence of the so-called independent curator, who works as a freelancer for multiple institutions.

Szeemann’s departure from his position as director at the Kunsthalle Bern, following his 1969 exhibition Live in Your Head: When Attitude Becomes Form, is frequently cited as the advent of the independent curator. The form of Szeemann’s exhibition mirrored the work it featured, emphasizing process and approach over object or result. He had planned to turn the Kunsthalle into a giant studio and invited close to thirty artists to Bern, which “became as much an international meeting place and discussion center as a workshop.”2 The art in the show exceeded the gallery spaces, engaging hallways and staircases, and spilling out into the city streets. Despite its current fame, when the show opened, it met strongly negative reactions from the conservative Swiss audience, which was outraged that public funds had been spent to support work that it deemed abominable. Bags of excrement were left on the Kunsthalle’s front stairs, Szeemann received threatening letters— and the Kunsthalle’s trustees’ distressed response to this outcry led to his resignation and decision to begin an independent practice of organizing projects for a variety of museums, biennials, and other venues. In this way, Szeemann extended the work of exhibition-making not only beyond the conventional mediating functions of the curator, but also beyond the programmatic functions of the institution. The latter reinforced the former, since, as Calderoni notes, he laid claim to autonomy not in support of a definite artistic tendency—to the contrary, his taste was decidedly eclectic—but rather as necessary to the poetics of his own practice, as “a project of meaning” (CS, 76).

While Szeemann’s career perhaps has been mythologized, similar stories might be told about the careers of other seminal curators from the 1960s, including Jan Leering and Walter Hopps; and, in recent years, the demand for such free agents has increased as exhibitions have proliferated and developed into ever more ephemeral events, divorced from particular collections. But the autonomy of the independent curator should not be exaggerated. Hoffmann is careful to qualify: “Most independent curators are indeed independent simply because they cannot find a position in an institution and not because they believe in the idea of independence, in the true sense of the word, or for political principles” (CS, 140).

If post-1960s models of site-specificity and process-based art provided one key trajectory challenging traditional exhibition practices, another was the growing importance during the 1980s of postcolonial and postmodern discourses, with their sustained examination of the defining exclusions of museum collections and the ideology of the Western canon that informed these exclusions. The Korean curator Young Chul Lee proposes that, “When Attitudes Became Form was a very important exhibition that signaled the beginning of international exhibitions, but also the peak of Eurocentrism” (CT, 112). The Argentina-born Philadelphia Museum of Art curator Carlos Basualdo notes that while “an exhaustive revision of the canon and a reexamination of the autonomous nature of the work of art are actually two sides of the same coin,” the expansion of exhibition practices to address the geographically broader social, political, and cultural conditions of art-making was rarely undertaken before the 1980s (WMGE, 59, and CS, 49). Specifically, Jean-Hubert Martin’s controversial 1989 Pompidou Centre exhibition Magiciens de laTerre remains a decisive juncture in the genealogy of contemporary curatorial practice. As the New Delhi–based critic Geeta Kapur explains, the exhibition situated “Europe’s perennial interest in the exotic within the new translucent permissiveness of the postmodern. In Magicens, Martin gave something like a ritual status to contemporary avant-garde art of the west, relating this to the allegedly magic-driven artworks from ‘other’ cultures” (CT, 58). While the exhibition was widely criticized from various perspectives, it nonetheless played an important role in challenging the geographical boundaries that until then had defined the art world.

In hindsight, given the globalization of contemporary art in the past twenty years and the explosion of international biennials, such a move might seem inevitable. Nevertheless, the issues at stake remain hotly contested. For many, the current, largely market-driven globalization is an insidi ous phenomenon, directly related to the neo-liberal expansion of deregulated capitalist markets since the end of the cold war. Strauss notes that Szeemann, for instance, “saw globalization as a euphemism for imperialism, and proclaimed that ‘globalization is the great enemy of art’” (CT, 23). In a similar vein, the critic Robert Nickas (in CS) levels a series of by-now-familiar attacks against biennials as vehicles to promote cultural tourism, which although broadening the audience for contemporary art, ultimately subordinate art to political and business interests. As the Swedish curator Sara Arrhenius acknowledges, in bienni als “art has quite openly become part of a culture-and-entertainment industry,” which serves the express ends of “nation, city, or region branding” (CT, 100, 102). Okwui Enwezor defends biennials against such critiques because they infuse “a new sense of the contemporary in cultures that did not or do not have an institutional legacy to carry it forward” (CS, 116). Decrying the implicitly separatist and exclusionary practices prior to globalization as “the colonial, Jim Crow and apartheid days put together” (CS, 110), he argues that international biennials provide crucial opportunities to reconsider modernity and modernization. Against the claim that biennials tend to homogenize works from disparate places and traditions, he reaffirms their diversity in opposition to the relative uniformity of more conventional institutions, like contemporary art museums, which, he claims, all collect the same artists.

This debate marks one particularly vivid point of contention in broader discussions concerning the aesthetics and politics of contemporary art. With the dissolution of the autonomous work of art and the assimilation of previously avant-garde practices by cultural institutions, contemporary art would seem to have lost the oppositional position that, for many, gave art its force and meaning since at least the nineteenth century. However, simply to dismiss these developments would fail to recognize their potentially transformative implications. Clearly these questions exceed the scope of this review. But they contribute to explaining why, as Basualdo contends, biennials present something of a crisis for contemporary art criticism, and how curators both fill the gap left by this critical void and, in it, find much of their new prominence and creative authority.

As cultural institutions, biennials are not defined exclusively or even primar ily in the art historical terms conventional to museums, nor do they conform to the model of commercial gallery exhibitions. Instead, their funding often derives from governmental or tourist initiatives, and they frequently serve diplomatic, political, and economic ends. Thus unlinked from collection-based institutions, biennials often support the production of non-object-based, interdisciplinary works drawn from eclectic fields. Artworks are often displayed in conjunction with discussions, screenings, and other events that are too extensive or ephemeral to be viewed in their entirety. Given this often vast, spatial and tempo ral diffusion, the intellectual cohesion of biennials ultimately lies in the highly particularized interpretative systems pro- vided by curators. Based on extensive travel and an inherently deterritorialized model of expertise, as Basualdo concludes, “The type of knowledge [biennial curators] put into practice becomes less and less retrievable from the perspective of the critic or art historian” (WMGE, 59, and CS, 49). Biennials are “unstable institutions” that call for curators to provide at least the appearance of unity. While curators may frequently be overvalorized in this new role, the responsibility granted them for these complex and ultimately underdetermined events not only enables, but requires them to articulate their own visions.

As artists have turned to mounting installations and organizing shows and social encounters, and curators have produced creative projects of their own, the divisions of labor in contemporary art have broken down. Not surprisingly, this has frequently resulted in strife.The Dia curator Lynne Cooke (WMGE, 32) recalls the section of a 2003 catalogue, produced by students in the Royal College of Art Curatorial Studies program, titled “The Undeclared Struggle between Artist and Curator,” which took as its point of departure the premise that recent art practices represent a threat to the curator’s professional freedom and proficiency. On the other hand, contemporary curators are often criticized for treating artists merely as instruments for their own curatorial visions. Geeta Kapur, for instance, describes Catherine David’s Documenta X—without evaluation—as “exceed[ing] the artists’ intent” in order to make a broader philosophical case concerning “what critical contemporaneity in art might mean today.” (CT, 58) Since at least the 1970s, artists and critics have more forcefully taken issue with shows that seem to “turn the cura- tor into the main artist,” including Jack Burnham writing about projects by Lucy Lippard and Seth Siegelaub, Les Levine on Kynaston McShine (curator of Information), and Daniel Buren in his infamous critique of Szeemann’s 1972 Documenta, effectively titled “Exhibition of an Exhibition” (quoted in Calderoni, CS, 78).

Utopia Station Venezia Utopia Station Venezia / 2003 / Materials: wood, mixedmedia / dimension variable / Courtesy: Biennale di Venezia, Venice.

These conflicts are very real and far from resolved. Rather than simply tak ing sides, we might do well to recognize their defining condition in the fluid—if somewhat idealized—dynamics that Liam Gillick describes in his reflections on the exhibition Utopia Station, organized by Hans Ulrich Obrist, Molly Nesbit, and Rirkrit Tiravanija for the 2003 Venice Biennale. Coming together for this project, the organizers are better known as a curator, an art historian, and an artist, respectively, and this complication of roles extended to the show itself. According to Gillick, theorists who thought they were commenting on the show, at times, were in fact contributing to its structure as they spoke, while many artists were invited only to contribute a single poster to the event and so, rather than playing a central role in the exhibition, “simply formed a particular new kind of implicated ‘audience’ for the multiple events” (CS, 125). In his heroicized account of this new fluidity and dispersion of roles, Gillick recounts how many people who contributed to the show “just happened to be around during a dinner or discussion and limited their role to that one night of confusion or clarity” (CS, 125). Although Utopia Station represents one extreme of redistributed exhibition practice, and Gillick’s account neglects crucial issues, like the sources of economic support that make such practices possible, he nicely captures the fundamental condition of exhibition-making now as both underdetermined and so, broadly speaking, experimental.

In “Futures: Experiment and the Test of Tomorrow” (CS), the NewYork–based art historian and critic Eva Diaz explores this experimental paradigm for thinking about how exhibitions now complicate disciplin- ary distinctions. She takes as her point of departure Obrist and Barbara Vanderlinden’s 1999 show Laboratorium, which brought together artists and scientists to collaborate on projects. While acknowledging the contradictory implications of this “laboratory” model, Diaz locates their common experimental basis in dissatisfaction with present conditions and—connecting contemporary curatorial practices to the history of modern art—explains experimentation as a matter of “not necessarily rupturing or transgressing the symbolic order,” but rather testing “the limits and adequacy of representation to depict or inform the conditions of society” (CS, 97).

Of course, by describing contemporary exhibition practices as experimental, one risks the implication of objective distance characteristic of empirical research. But this presumption of neutrality is exactly what has been compromised, and much of the debate about contemporary curat ing concerns the hermeneutics of display in broad theoretical terms that far exceed the conventional discourse on exhibition design. Furthermore, to explain contemporary exhibition-making as underdetermined, and therefore experimental, is not to say that it lacks any determination at all. To the contrary, it recognizes that the determining conditions of exhibitions are manifold and frequently conflicting—divided not only between the competing visions of artists and curators, but also by the imperatives of the art market and the many other public and commercial demands that exhibitions now serve, including tourism, urban regeneration, and political prestige. Their underdetermination lies in the fact that these competing forces are not uniform and cannot be accommodated within a univocal ideological framework. They assume different forms for different shows and different venues—and the organization of exhibitions now entails constantly renegotiating their diverse demands. The Dublin-based curator Sarah Pierce makes this point in terms of attention to the local, which she defines as the complex circumstances that inform any exhibition, carefully distinguishing the relative underdetermination of contemporary exhibition-organizing from “the vagaries of practices where ‘anything goes’” (CS, 162). Similarly, the breakdown of museum- and gallery-based conventions of exhibition does not exhaust the artistic models of institutional critique that historically played essential roles in foregrounding their institutional frame. To the contrary, as Arrhenius contends (in CT), the discourses and practices of institutional critique, which, in the hands of artists like Haacke, Michael Asher, and Andrea Fraser remained focused on museums and commercial galleries, need now to turn their attention to the new conditions of artistic exhibition and distribution and the more diverse and sometimes veiled institutions that sustain them—as artists like Santiago Sierra already have begun to do.