Nicholas Nixon: About Forty Years

This piece was published in Afterimage: Journal of New Media and Cultural Criticism. The original can be found here, or this post can be cited as: Buckner, Clark. “Nicholas Nixon: About Forty Years”, www.clarkbuckner.com. Web. Day, Month, Year the post was accessed.

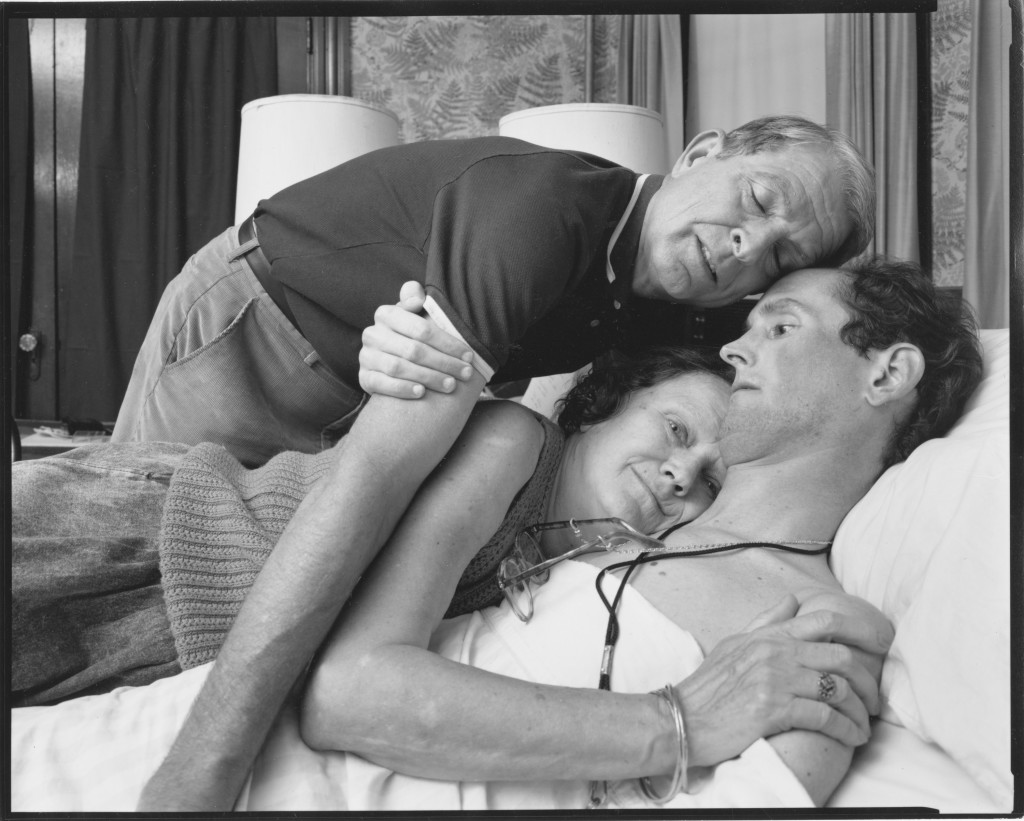

Robert Sappenfield and His Parents, Dorchester Massachusetts, 1988, c-print, © Nicholas Nixon, courtesy of Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

Wandering into Fraenkel Gallery, I was unexpectedly struck by an image in this show of Nicholas Nixon’s large format, black-and-white photographs. The picture hung alongside two others that were also taken in the late 1980s during the height of the AIDS crisis in the United States. In the first photograph, George Gannett, Barrington, Rhode Island (1989), a man lies sleeping beside a window. With his gaunt head hanging backward and his mouth agape, he is visibly exhausted. Medical equipment fills the room as testimony to death’s banalities. There is nothing romantic about the image. Yet, the rich grays in the picture are also invested with the meditative silence of the photographer’s presence, and the light streaming through the window, at least, holds out the promise of the man’s eventual release. The next picture, Donald Perham, Milford, New Hampshire (1988), features the emaciated figure of a middle-aged white man with a salt-and-pepper beard. As he leans forward in his chair with his arms on his knees, his bony ribcage carves a vertical arc across the picture plane. His head is turned slightly toward the camera, and his gaze is turned inward as if he has been caught in a passing moment of reflection on the past.

Images of the AIDS crisis are familiar, but the tender intimacy of Nixon’s pictures sets them apart. In the photograph that caught my attention, Robert Sappenfield and His Parents, Dorchester, Massachusetts (1988), a man in his early thirties lies in bed with his glasses hanging down from around his neck and the sheets pulled up over his chest. The young man’s father leans down and rests his temple against his son’s forehead. With his eyes closed and his lips pursed, the older man has a look of profound love and sadness on his face. His arm extends over his son’s torso, while the younger man reaches up to clasp his father’s bicep. Between them, the young man’s mother lies with her face against her son’s chest. She reaches across his body to hold his shoulder, looks directly into the camera lens, and smiles. Along with welcoming the photographer into the scene, the mother’s smile conveys a pride and happiness that defies both the stigmatization of AIDS victims and the voyeuristic anticipation of maudlin grief. There is great joy in her love for her son, as much as sadness in his impending loss. Or, rather, the two are the same, crystalized in her visage.

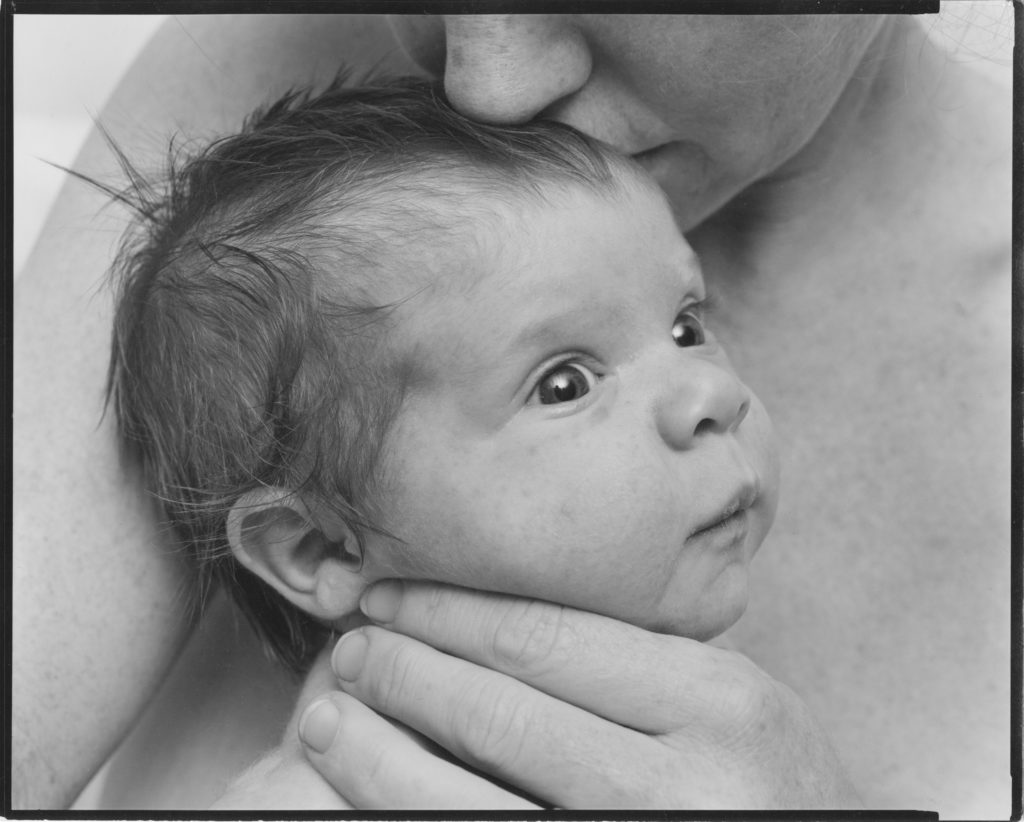

As much as a document of the AIDS crisis, Nixon’s picture captures the love of a family. Resting against one another, the three faces comprise a whole, reinforced by the geometric pattern of their interlocking arms and hands. The image is almost archetypical, faintly resembling an African woodcarving or symbolist painting. As the portrait of a family, the photograph also finds its place among Nixon’s other work. At the center of Nixon’s photography is life’s passage through time, which he explores with a distinctly materialist attention to the vicissitudes of the body and the changing dynamics in intimate, personal relationships, marked by the passing of generations. Nixon is best known for an ongoing series of pictures, The Brown Sisters (1975–present), that he has taken of his wife Bebe and her three sisters, once every year, over the past forty years. With the four women consistently arranged in the same order, the pictures capture their shifting attitudes and relationships to one another as they age over time. Other works in the show at Fraenkel Gallery, similarly, evidenced Nixon’s attention to intimate, often familial, relationships, and the stages of life. Immediately to the right of the pictures from the AIDS crisis was a series of closely shot photographs of nude bodies in loving embraces. On the neighboring wall were two pictures of sublimely old men, along with a photo of a newborn in its mother’s arms, and another of naked kids goofing around. On the opposing wall, there were pictures of a young couple relaxing outdoors, brothers wrestling beneath a tree, an old man walking alone in fall, and various configurations of children with their siblings, friends, parents, and grandparents.

As a chronicle of aging, critics have noted, Nixon’s pictures of the Brown sisters are haunted by the specter of mortality. The photographer makes the point himself, when he explains his intention to “go on forever, no matter what. To just take three, and then two, and then one.” He adds, “The joke question is: what happens if I go in the middle. I think we’ll figure that out when the time comes.”1 In fact, the insight might be extended to all of Nixon’s pictures, as documents of discrete moments in the process of life’s coming to be and passing away. Strictly speaking, however, losing a child is not a stage in the natural cycle of life and death. It does not belong to the passing of generations, but rather marks an interruption in the process. Furthermore, the AIDS crisis was too political—one might say, too historical—to abstract its unfolding as merely characteristic of our finite condition. Accordingly, Nixon’s Robert Sappenfield and his Parents might seem to stand apart from the rest of his work. Indeed, it might seem to reveal a blind spot in the artist’s view of the world, as naively divorced from social and historical realities in its attention to intimate, domestic relationships and the exigencies of time.

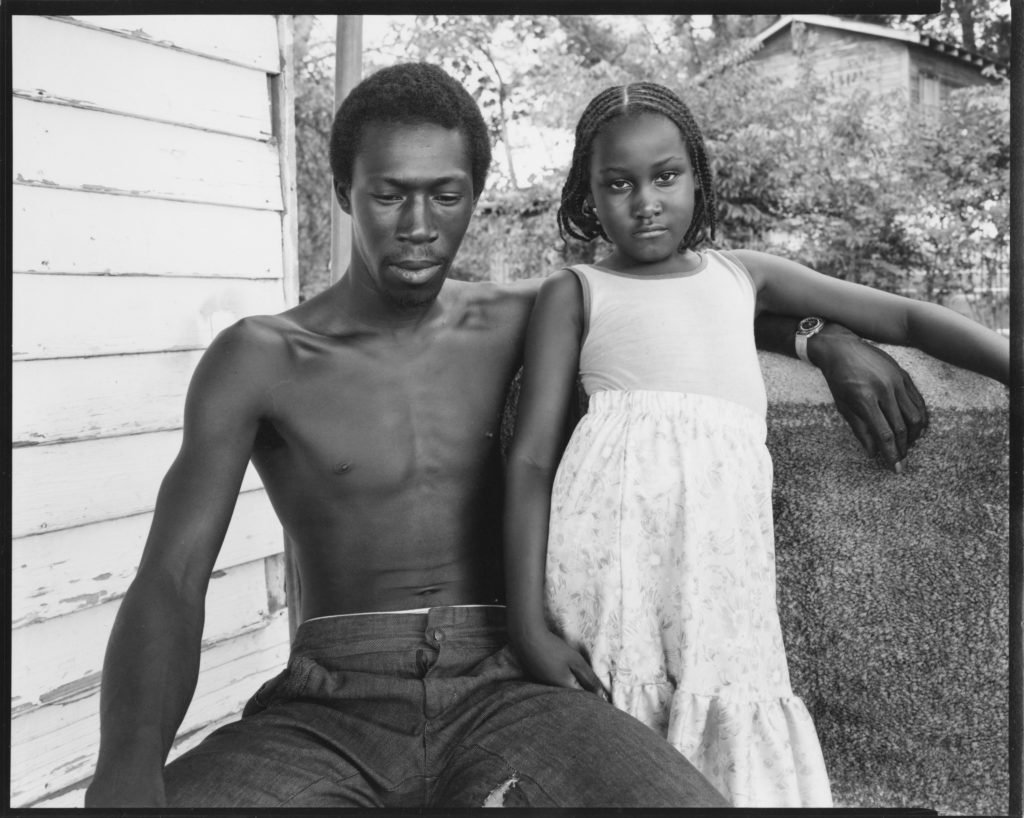

To the contrary, however, evidence of history can be discerned throughout Nixon’s oeuvre. In Along Memorial Drive near M.I.T., Cambridge (1979), for example, a young white boy sits at the edge of Boston Harbor with his grandfather. They’re both shirtless, and their postures are humorously similar. In fact, they almost appear to be different instances of the same man: the boy, an old man in miniature, and the grandfather, an overgrown kid. But the domestic scene is not set apart from the broader world. The grandfather’s arms and chest are covered with decidedly working-class tattoos. The natural idyll, there beside the bay, bears evidence of the harbor’s industry. And the city of Boston rises up in the background. Similarly, in Yazoo City, Mississippi (1979), a dark-skinned African American man sits outside his home with his shirt off and his arm around his daughter. His eyes are cast downward toward the floor, while she leans into his side and stares back at the camera. As a study of the personal relationship between this father and daughter, the differences in their respective stations in life, and the ways in which these are manifested in their physical comportment, the photograph, once again, is terrifically intimate. But it also speaks in subtle ways to the social conditions of their family life. The young father’s pants are torn. The paint on the outside of their home is peeling off. And, although the young girl obviously takes strength from her father’s supportive presence, his downcast gaze would seem to attest to the challenges that he confronts in his efforts to make good on his everyday responsibilities.

As evident in the titles of his pictures—F.K., Boston (1984); S.V., R.I., Cambridge (2001); John Royston, Easton, Massachusetts (2006)—Nixon situates his subjects against the background of the cities where they live. While attending to the details of their personal relationships, he simultaneously captures the ways in which they have been marked by broader social and historical forces; and, without thereby reducing personal life to the political, he presents intimate relationships as the context in which the exigencies of history hit home. And isn’t this, indeed, how poverty and injustice are suffered, in the limits that they put on people’s personal lives? Isn’t this what made the AIDS crisis in the 1980s United States so urgent for activists, the sudden loss of so many young lovers and friends? And what could make this history more vivid than Nixon’s remarkably intimate picture of the Sappenfields embracing their son?

NOTE 1. Sean O’Hagan, “We Are Family: Nicholas Nixon’s 40 Years Photographing the Brown Sisters,” the Guardian, Nov. 19, 2014.