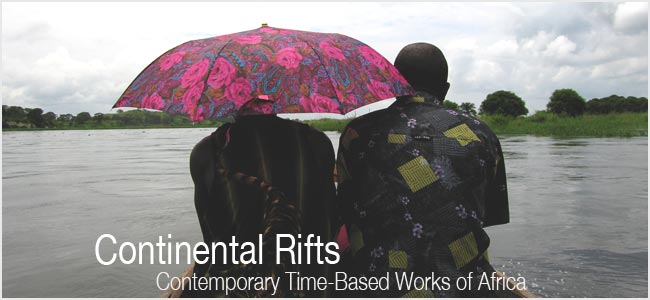

“Continental Rifts: Contemporary Time-Based Works of Africa,” at the Fowler Museum

This piece was published in NKA: Journal of Contemporary African Art. A copy of the original can be downloaded here, or this post can be cited as: Buckner, Clark. “Continental Rifts: Contemporary Time-Based Works of Africa at the Fowler Museum.” www.clarkbuckner.com. web. Day, Month, Year the post was accessed.

Geography is not defined by physical topography alone. Territories bear the marks of their histories, the struggles that have distinguished one place from another, and the social and psychological dynamics that inform our relationships. The exhibition at UCLA’s Fowler Museum, “Continental Rifts: Contemporary Time-Based Works of Africa,” presented video, film, and related photography by five celebrated contemporary artists who engage these complex dimensions of geography and the ways they are mediated aesthetically.

Specifically, the show focused on the African continent but from various global perspectives, including works by artists who live in Africa, a European artist with roots on the continent, and a New York–based South American artist who frequently works in Rawanda and Angola. As captured in the somewhat awkward phrasing of the title, it was not a show of works about or from Africa, but rather of Africa, holding open the possibility of more diverse ways of relating to the continent and, at times, explicitly pressing the question of the nature of belonging implied by the genitive. In this way, the show specifically accommodated the legacies of both colonialism and the African diaspora; and the works in it consistently presented the continent not as a static landmass, but as changing in light of the shifts in perspective produced by movements to and from it, under the force of history.

South African artist Berni Searle’s two-channel video installation, Home and Away (2003), for example, is above all about direction. One screen features an image shot from a small boat with an outboard motor, leaving behind itself a foaming wake as it pulls away from a coastline in the distance; on the other screen, a woman floats on her back in the ocean, wearing a tank top and loose skirt with layers of white, pink, and red. Accompanying the sound of the lapping water and the roar of the boat’s engine, an overdubbed voice conjugates the verbs, “to love,” “to fear,” and “to leave.” The two juxtaposed images were shot off the coasts of Spain and Morocco respectively, bringing into dialogue these two physical borders and evoking the history of migration between them. But nothing in either image identifies its location as such, and the piece ultimately addresses more formal, phenomenological issues of orientation. The boat racing over the ocean moves from and toward, while the woman on her back floats in a space suspended between. Flanked by the two opposing images of the installation, the viewer similarly is suspended in an always-intermediary situation, deprived of any vantage from which to view the piece as a whole, and required to turn his or her attention one way or another. While initially I found the mantra of conjugating verbs somewhat ponderous, ultimately it enriches these phenomenological dynamics, by presenting them not merely as formal intentional structures, but furthermore as affectively loaded and informed by anxiety and desire.

For her single-channel video projection, Africa Rifting: Lines of Fire: Namibia/Brazil (2001) the South African artist Georgia Papageorge employs long swatches of deep red fabric to engage, accentuate, and juxtapose the aesthetic wealth of the coasts of Western Africa and South America. In one series of closely shot images, Papageorge’s camera moves across the surface of the rich red cloth as it extends from green foliage into the sand, finally to be washed over by sea foam. In a second sequence the fabric is shown from a distant, wide angle, hanging off a high, steep rock cliff, and extending over grass, sand, and other rock formations, out to the beach. A third series of images presents shorter cuts from the cloth, mounted as banners on T-bar poles—first three and then as many as seven or ten—and blowing in the wind against backdrops of dunes and crashing surf. In diverse ways, the cloth highlights the dynamics of the landscape. Its folds and shadows mirror the curves and crevasses of the rocks and sand. Its movement articulates the currents of wind and water. Its rich red contrasts with the green of the shrubs and beach grass, the gray of the stone, and the deep blue, white, and tan of the sand and ocean.

The piece was shot both on the barren Skeleton Coast of Namibia and on the beaches of the coastal Brazilian city of Torres. Accompanying text in the exhibition brochure explains it as “a portrayal and re-imagining of the Gondwanaland Split—commencing 135 million years ago and producing two land masses that would become South America and Africa.” In this light, the cloth reads like a tear or scar—evoking the blood of a wound—that divides and conjoins the land it intersects. The piece takes on a decidedly psychological tone as a meditation on separation, loss, and reconciliation. In another, closely related project (not presented as part of this show), Papageorge uses the red cloth again as what accompanying text describes as “a moveable artery in processions and performances aimed at transforming wounds of separation.” However, Papageorge’s projection is decidedly abstract. Despite its site specificity, the piece includes no concrete historical references. If it evokes themes of traumatic division, it does so from a vantage that remains untroubled by the ordeals it means to address—as if reassuring its viewers that the wounds in question have been healed before allowing the viewers to suffer them.

In contrast, Chilean-born artist Alfredo Jaar’s digital film Muxima registers the difficulty of representing history and its traumas through a critically self-conscious engagement with the limits of its media. The film, which was shot in Angola, is organized like a poem, in a series of ten cantos. Each one is a meditation on a sequence of images, which sometimes coalesces into a loose narrative. But the significance of each canto and the work as a whole remain decidedly underdetermined, leaving the viewer to reflect on what exactly he or she has seen and what it might have meant; and, despite the film’s many documentary elements, its force ultimately lies in this poetic resonance.

One canto features only a single still image of six boys, posing together with their hands across their chests in a kind of impromptu and markedly informal salute. Another canto juxtaposes images of a shantytown, the ruins of a World War II–era jet fighter, and crumbling white marble statues of colonial Europeans. In a third, close-ups depict a man walking through green foliage: his boots step on and over plants, his hands reach down to pull weeds and cut them with a scythe. These images are then intercut with elegant pictures of a yellow microphone against the background of red stained wood. Back in the foliage, the close-ups continue, now presenting a metal detector, whining like a theremin as it moves over the ground. The man is shown with a transparent safety mask over his face. We cut back to the microphone: a man now stands behind it with a beard and a hat. And boom! Something explodes. The camera momentarily withdraws far enough from the foliage to reveal a small red Danger sign planted in its midst: a minefield. And the man behind the microphone begins to sing.

How are we to understand these images and their juxtaposition? The film clearly speaks about Angola’s history and the struggles of its people. But what are we supposed to think about them? Among other ways, the piece presses these questions—as a set of formal problems integral to its composition—through its soundtrack. Its title, Muxima, is also the title of a popular Kimbundu folk song with a simple, descending melody that is repeated throughout the film. When juxtaposed with distinct images in each canto, the song resonates differently, revealing its intrinsic complexity and the underdetermined significance of both the pictures and the music. However, Jaar’s film does not thereby degenerate into mere relativism. On the contrary, Jaar clearly works to articulate truths even as they prove elusive, complicated, and approachable only through indirection. His film exhibits a formal self-consciousness about how to represent its subject matter, which accompanying text explains as motivated in particular by the mass media and the numbing sensationalism of its purported immediacy. At the same time, Jaar’s repetition of the song “Muxima” also avoids becoming a merely formal exercise. The song is performed differently each time—with mournful soul by the man singing behind the yellow microphone, with an upbeat tempo on Afro-pop guitars, with urban syncopation on solo jazz piano, and so on. And these diverse renditions combine with the images in the various cantos to give the film a rich, poetic sophistication.

In her seven-channel video installation Fata Morgana, Claudia Cristovao approaches Angola with still greater indirection. Cristovao was born in Angola to Portuguese parents who immigrated to Portugal when she was still a child. For Fata Morgana, she interviewed other people with similar personal histories, who express strong identifications as Africans and powerful associations with the continent, despite the fact that they only have faint memories of it. Rather, they know Africa through their families’ mythologies, the stories they recount, the customs they have brought back with them, and the community they share with other Portuguese people who previously lived there. These interviews were shown on several small screens hanging from the ceiling, and were accompanied by two larger projections that featured images of abandoned buildings and other structures in a colonial African ghost town from the early twentieth century, which slowly were disappearing beneath desert sands. “Fata Morgana” means “mirage” and Cristovao’s piece is above all about memory and the ways in which fantasy serves to fill the voids produced by loss and longing. In her installation, Angola appears largely as a mythical country of origins, a stand-in for the remote land of childhood that lingers in the back of each of our minds and plays a key role in our sense of who we are, despite its elusive distance. At the same time, Cristovao’s interlocutors attest to the actual history of colonialism and its wake. They present how personal fantasies frequently are intertwined with broader social-historical conditions and vice versa; and they show how modern identities frequently are formed across international and even intercontinental borders.

If, among other things, Cristovao’s work addresses nostalgia, Paris-born Moroccan artist Yto Barrada mobilizes similar feelings for political ends in her film The Botanist and related photography. The film features an informal tour of a botanist’s garden, shot almost exclusively with the camera aimed at the legs and feet of people passing through its flowers and greenery. On the sound track, a guide can be faintly heard identifying the many varieties of indigenous and endangered plants growing in the garden and making occasional references to the threat presented to them by commercial developments in the area. These commercial developments are also featured in Barrada’s photographs, and accompanying text explains the work as a protest against them. The flowers stand in as figures for “old Morocco,” apparently compromised by the burgeoning tourist industry. But the injustices at issue in Barrada’s film remain decidedly undefined. The piece relies on a romantic juxtaposition of the native earth with sinister forces of civilization that obscure any appreciation of the social conflicts currently taking place in Tangier beyond a broad and ultimately apolitical concern for the environment—which paradoxically might have been shared just as easily by the tourists she apparently deplores.

If one were to have confused Continental Rifts with an exhibition of time-based works about Africa, clearly it would have left something wanting. And one can imagine how the exhibition’s subtle curatorial premise of approaching Africa from diverse global perspectives risks supplanting the claims of artists from Africa. However, taken on its own terms, as a study of the complex dynamics at play in the constitution of geography, the show provided a rich survey of works whose media combined visual, musical, and poetic art forms to address the complicated affective and ideological aspects of the sense of place. The strongest pieces in it register a deep sense of history—not only in content but also in form.

This review was published in NKA: Journal of Contemporary Art, Number 25, Winter 2009, pp. 163-165. Download a pdf copy here or on the journal’s website, or cite this post as:

Buckner, Clark. “Continental Rifts: Contemporary Time-Based Works of Africa.” Resonator. Web. Day, Month, Year article as accessed.