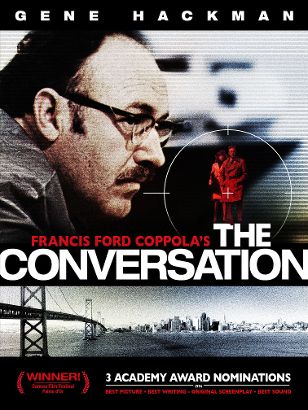

The Surplus Enjoyment in Banal Evil: Arendt After Coppola’s The Conversation

These reflections were presented as part of the Annual Winter Immersion at The Lutecium School of Lacanian Psychoanalysis. It can be cited here as: Buckner, Clark. The Surplus Enjoyment in Banal Evil: Arendt After Coppola’s The Conversation. www.clarkbuckner.com. Web. Day, Month, Year the post accessed.

The Conversation centers on the surveillance audio recording of a surreptitious exchange between adulterous lovers in San Francisco’s Union Square. Harry Caul has been hired to tape the couple. He is a professional eavesdropper, a wire-tapper, or, as one character pejoratively calls him by the appropriately professional euphemism, “a surveillance and security technician.” (DVD, 51:46) In fact, we learn he’s among the best in the business; and he manages to capture the exchange, despite the many obstacles that they, knowing that they are being followed, intentionally put in his way – an accomplishment that his assistant, Stan (John Cazale), later celebrates as “a work of art.” What drives the plot and defines the central problem in The Conversation is Harry’s sense of responsibility for his work – or, rather, his disavowal of any responsibility for it. In the very first scene, as the lovers’ exchange is being taped, Harry responds to Stan’s passing curiosity about what the young couple might be discussing by declaring, “I don’t care what they’re talking about. All I want is a nice fat recording.” (DVD, X) Harry insists that he is merely a technician, an expert in the art of surveillance recording with no concern, interest, or responsibility for the content of his tapes. He repeatedly declares that what his clients do with his recordings is not his business. However, as the film develops, Harry indeed becomes concerned about the ends to which his tapes might be used. His tapes, it seems, previously contributed to a murder; and, again in this case, he fears that his work may bring harm to the couple or, more specifically, to the apparently unfaithful young wife for whom, from a distance, Harry develops a strong affectionate attachment. Despite his insistent declarations of neutrality, he involves himself in the substance of the case, which does indeed result in murder. However, contrary to Harry’s fears, the apparent lovers are not the murder victims; they are the murderers, who self-consciously exploit the fact that they are being taped to lead Harry’s client, the cuckolded husband from whom he thinks he is trying to protect them, into a trap. And Harry ends up at their mercy, subject to their surveillance and threatened against telling anyone about the crime.

What then is the nature of Harry’s responsibility and how does it inform all that unfolds in the film? In what follows, I firstly pursue this question by entertaining the critique leveled in the film against the immorality of instrumental reason – or, what Hannah Arendt famously describes as “the banality of evil.” Harry’s insistence that he is only a technician and so bears no responsibility for the consequences of his work is clearly a centerpiece of the film. However, Harry’s sense of guilt precedes and exceeds the questions that he obsessively ponders about the potential consequences of his work. His guilt is integral to his work and to his character. Before and beyond any question of the potential uses to which his tapes might be put, I therefore examine Harry’s “merely technical” surveillance work as itself invested with unacknowledged enjoyments, which I also trace in and through other aspects of Harry’s life and elaborate with particular regard to his response to this particular case. I argue that the surplus-enjoyment provided by Harry’s otherwise banal work as a surveillance technician not only better explains Harry’s guilt, it furthermore suggests that he derives a degree of satisfaction from it. And, I conclude that the potentially violent consequences of Harry’s work plague him not because, by just doing his job, he is failing to exercise his judgment concerning its ultimate value, but rather because the violence too closely realizes the value that his otherwise banal labor implicitly holds for him.

- Beyond the Banality of Evil

Harry first becomes overtly involved in the substance of the case surrounding the conversation he records when his attempt to fulfill the surveillance contract proves more complicated than he expects. After distilling his multiple recordings into unified legible tapes, he arranges to deliver it to his client (Robert Duvall), the Director of a major business enterprise, whom he eventually infers is the cuckolded husband of the young woman. However, contrary to their agreements, the Director isn’t there to accept the tapes in person; and, when Harry hesitates to give them instead to the Director’s Assistant (Harrison Ford), the assistant tries to tear the tapes physically from his hands. “Don’t get involved in this Mr. Caul. These tapes are dangerous. You know what I mean. Someone may get hurt.” (DVD, X) Immediately following this altercation, Harry then sees each of the young lovers in the same building and rides the elevator down several floors with the unfaithful wife. As they stand there together in the tight quarters of the elevator, Harry awkwardly holds the tape in his hands, self-conscious that unbeknownst to her he knows (or thinks he knows) her secrets, and wary now – in light of the assistant’s threats – that this knowledge may contribute to her harm.

Despite having completed the job to his satisfaction, Harry then

After Harry’s attempt to deliver his tapes of the conversation results in a physical altercation with his client’s assistant, who insists in violation of the contract on receiving them himself and threatens, “Don’t get involved in this Mr. Caul. These tapes are dangerous. You know what I mean. Someone may get hurt.” (DVD, X), Harry goes back to studying and refining the recordings, now motivated solely by his own concern about the content of the case. Simply making small talk, Stan remarks, “What the hell are they talking about for Christ’s sake?” Harry irrupts with a disproportionate irritation, attacking Stan for asking him so many questions and denouncing his work as sloppy. “We’d have a much better track here,” he declares, “if you’d paid more attention to the recording and less attention to what they’re talking about.”

Stand responds, “Well, I can’t see how a couple questions about what the hell is going on can get you so out of joint?”

To which Harry replies, “Cause I can’t sit here and explain the personal problems of my clients.” (DVD, X)

Of course, trying to explain his clients’ personal problems is exactly what Harry has begun to do; and Stan’s questions irritate him because – unbeknownst to Stan – they speak so directly to Harry’s conflicts. But what is the source of these conflicts?

This case reminds Harry of another, which he first introduces while only half-truthfully confessing his sins to the attentive ear of a priest.

I’ve been involved in some work that I think will be used to hurt these two young people. This happened to me before. People were mur… hurt because of my work. I’m afraid it could happen again. I was in no way responsible; I’m not responsible. For these and all the sins in my past life, I’m heartily sorry.

Later he details of this prior incident are spelled out more completely. Harry was working for the Attorney General. The president of a Teamster Local had set up a phony welfare fund. Only two people knew about the fund, the president and his accountant. They only talked about it on fishing trips on a private “bug proof” boat, and wouldn’t talk about it if they spotted another boat on the horizon. Nevertheless, Harry “recorded everything” to unanticipated, but nevertheless disastrous consequences. While Harry carefully notes that nobody knows what in fact happened, it seems that the corrupt president of the teamster local thought that his accountant had betrayed him. The accountant, his wife, and his son, were found in their home tortured, murdered, and mutilated. While the story is being told, Harry interjects, “It had nothing to do with me. I just turned in the tapes.” And later he continues, “What [my clients] do with the tapes is their own business… It had nothing to do with me”

In light of these conflicts, The Conversation appears to indict the immorality of instrumental reasoning, in the same spirit as Hannah Arendt’s reports on the trial of Adolf Eichmann, the bureaucrat who played a pivotal role in orchestrating the Holocaust. Harry is no savage, motivated by passionate violent urges. He is highly rational, a technological wizard, responsible for innovating new designs and capable of unrivaled accomplishments in his field. However, Harry’s very rationality – the rigor of his calculations as objective and divorced from any distorting teleology – itself appears to undermine his moral judgment. He’s “just doing his job,” fulfilling his contracted obligations; but his exclusive attention to such means and ends blinds him to considerations of the ultimate value of his actions. At the same time, neither Harry’s work nor his self-justification is deviant but rather perfectly consistent with the prevailing standards of social morality. The Director’s Assistant too insists, “Our tapes have nothing to do with you.” A party girl named Meredith (Elizabeth Mac Rae), whom Harry meets at an industry convention, reassures him, “Forget it, Harry. It’s only a trick… A job. You’re not supposed to feel anything, you’re just supposed to do it.” (DVD, X) And, while Harry responds as if he’s being chastised, the colleague who later recounts the scandal of the accountant’s murdered family is really only interested in learning how he succeeded in tapping the conversation. Harry’s conflicts and failings, it seems, are emblematic of the immorality of modern technocratic society, and through him, Coppola levels a larger, social critique.[1]

However, the question of Harry’s responsibility for the potential consequences of his work is more complex than it first may appear. In the incident involving the president of the teamster local, Harry was working for a just cause. The violence erupted from a misunderstanding between the parties under surveillance and ran counter to the aims of Harry’s employers rather than realizing them. Harry may be in fact perfectly justified when he insists that the murders had nothing to do with him, despite the fact that only he was capable of recording the conversation that precipitated them. And, as already introduced, his involvement in the case at the center of the film only proves to be misguided. The Conversation thus presents a complex web of ethical problems. But even a more subtle treatment of the philosophical conundrum concerning Harry’s responsibility for the potential consequences of his work would fail to do justice to Harry’s sense of guilt, which permeates his character. Harry is a profoundly pious person. Along with attending confession, he keeps religious icons in his home and chastises others for taking the Lord’s name in vein. His guilt not only pertains to his work, it pervades every aspect of his life including most explicitly his personal relationships – or more precisely, his inability to sustain them. Even his name, Harry Caul, evokes both the moral call of conscience and the religious vocation through which, at least in Calvinism, one works to demonstrate one’s election. Any consideration of Harry’s sense of responsibility for his work thus requires that we reflect on its particular significance for him, in light of his already guilty conscience, and analyze the structures and dynamics of his work in surveillance before and beyond its application to any external end.

- The Guilty Pleasures of Eavesdropping

In The Conversation, these structures and dynamics are presented most explicitly by “Bernie” Moran (Allen Garfield), another “security and surveillance technician,” whom Harry meets at an industry convention. While only a minor character in this consistently sparse film, Bernie serves in it as something like Harry’s obscene double: the perverse compliment to his obsessional character, who explicitly portrays the fantasies that implicitly inform Harry’s work. While Harry consistently dismisses and distances himself from Bernie, the trade papers identify the two similarly as pre-eminent figures in the field. Bernie reinforces this identification by pronouncing them the best in the profession on the East and West Coast respectively. And Bernie proposes a partnership between the two of them with a desperation that establishes Harry not as above Bernie the wire-tapper, but above him as a wire-tapper. However, whereas Harry is reserved to the point of being stifled – which in this context serves him well as discretion and restraint – Bernie and openly embodies the unseemliness of the surveillance industry, whose principal product is the violation of privacy, and which in one form or another always involves distrust and dishonesty. He’s sleazy: a trashy, flashy, businessman, with a cheap suit and a cheesy mustache, who produces gimmicky gadgets for “catalog suckers.” (DVD, X)

Through Bernie, Coppola presents the enjoyment that informs and sustains surveillance, before and beyond its application to any external ends, as a subversive, adolescent, sense of power. During a party at Harry’s warehouse, following the conference where he and Bernie first meet, Bernie boasts, “You know, I tapped my first telephone when I was 12 years old.” What his motivations were, Bernie doesn’t explain; but later during the party he, Harry, and Meredith, listen in on a phone conversation that Stan and another guest are making. Under his breath, Bernie remarks, “I feel like I’m back in grammar school.” When they get caught, they all laugh it off. Divorced from any external, instrumental aims, wiretapping is a prank: the violation of another’s privacy in order, as we say, “to catch them with their pants down.” Under the right circumstances, even the target of a tap might enjoy the embarrassment it produces as humorous; but, even in its humor, surveillance clearly has an aggressive, even violent dimension, which more often provokes defensive anger.

Bernie sheds further light on the adolescent dynamics of power and subversion in surveillance, when he boasts that his work as a wire-tapper contributed to the defeat of a presidential candidate, proclaiming,

Twelve yrs ago, I recorded every telephone call by the presidential nominee for a major political party… Everywhere he went, I was there… Coast to coast, I was listening… I’m not saying I elected the President of the United States, but you can draw your own conclusions Harry. I mean he lost. (DVD, 1:02)

Bernie He presents surveillance as a surreptitious, even cowardly, form of stealing power from the powerful. To violate the privacy of another is to undermine their sense of composure and to deny them their authority – or, at least, the authority that one invests in them.

At the convention, Bernie stages a demonstration of one of his products, The Moran S15 Harmonica Tap, that paints a still clearer picture of these dynamics in surveillance. Planted in the phone of a target room; the tap can be activated and monitored remotely, turning the telephone into a room microphone. To entertain potential customers, Bernie pretends that he’s installed one in his own home. After he goes through the motions of triggering the microphone, voices can be heard through the receiver,

“Can we get away?”

“I don’t know.”

“Where’s your husband?”

“He’s out at a convention.”

“When will he be back?”

“Not until late.”

As a staging of, what one might call, the primal scene of surveillance technology, this stupid gag presents eavesdropping as riddled with sexual rivalry, envious insecurity, impotence, aggression, and erotic fascination. The eavesdropper is the jealous lover: the cuckold – like Harry’s client – who distrustfully, even accusingly, spies on his beloved, policing her desire. He’s a voyeur, pruriently fascinated by the intimacies of others, who takes pleasure in their violation. He’s the defiant child, excluded from his parents intimacies, who violates their privacy in order to steal back what he imagines he has been denied; or the punitive husband and father, who catches the illicit lovers in prohibited acts.

III. Harry’s Anxiety

If Bernie provides this portrait of surveillance as motivated, before and beyond any external aim, by the guilty pleasure of violating the privacy of others: a castrating rivalry that fetishizes intimacy, as if there were some such perfect union, and then stages its theft – does Harry too, despite his reserve, exhibit this enjoyment? Indeed, he does so precisely in and through his reserve. Whereas Bernie all but directly admits his prurient fascination in violating the privacy of others, Harry primarily demonstrates what the privacy of others means to him indirectly through the vehemence with which he guards his own.

Immediately following the opening sequence in which Harry tapes the conversation, Harry returns home to his apartment and, after unlocking the six bolts on his door, finds a birthday present left for him by his landlord. Rather than grateful, Harry responds angrily. He calls the landlord and interrogates her about how she got into his apartment. “I thought I had the only key,” he says, “Well, what emergency could possibly? …Alright, yes, you see I would be perfectly glad to have all my things to burn up in a fire, because I don’t have anything personal, nothing of value, nothing personal except my keys!!” (DVD, 12:20)

More profoundly, Harry manifests his anxieties about privacy and its violation in his inability to sustain relationships with others. When he visits his girlfriend, Amy (Terri Garr), she presses him, “Does something special happen between us on your birthday… something personal… like telling me about your self… a secret?”

He resists, “I don’t have any secrets”

But she challenges him, “I’m your secret.”

In fact, it turns out that she knows him better than he’d like, and knows some of his secrets. She’s seen him spying on her, hiding on the staircase and watching her as if waiting to catch her at something. When he comes over, he demonstrates the same suspicion: slipping his key into the lock as quietly as possible, before suddenly opening the door – again, as if he anticipates catching her in something. Sometimes, she adds, she thinks he’s listening in on her phone calls: a notion that she has no evidence to support, but which we have every reason to presume to be true.

While secretly spying on Amy, Harry simultaneously refuses to tell her anything about himself. When she persists in her attempt to get to know him, a gesture that he knows to be loving, he gets up in protest and before leaving, in a subtly aggressive, even insulting gesture, puts her back in her place and re-asserts the boundaries between them, by reminding her, “your rent is due,” and putting the money on her counter. For Harry, despite his feelings or perhaps because of them, it is – like Meredith says about his work – importantly only a trick. In sadness and frustration, she tells him that she won’t wait for him any longer, ostensibly ending their affair. Harry’s relationship with Stan breaks down along similar lines. Despite working together, the two don’t know each other. Stan is surprised when Bernie reveals that Harry comes from New York. As already cited above, Harry chastises Stan like Amy for asking too many questions; and it turns out that this is not an isolated incident, but fundamental to their rapport. When Stan exasperatedly leaves Harry to go work for Bernie, he complains that Harry doesn’t include him in the business, share his work, and bring him along in the profession. In his trade, like in his personal life, Harry is guarded to the point of being anti-social. Bernie jokes: “I was re-reading Dear Abby. There was a letter from lonely and anonymous. I think it was Harry.”

The light that Harry’s defense of his own privacy sheds on his violation of others’ becomes clearer still when Bernie pulls a prank on him. During the party at his warehouse, Meredith takes Harry aside, immediately tells him her whole life story “right up until tonight” and presses him to “trust” her. [DVD, X] For the only time in the film, he opens up, tentatively asking for her advice about Amy. Later, back with the others, while Harry and Bernie are playfully, if somewhat aggressively hassling one another, Bernie pulls out a tape recorder and plays a recording of Harry’s exchange with Amy. For Bernie, the recording was largely a joke and a demonstration of his technical prowess. He was oblivious to the content of the exchange; and the other party guests find the whole thing amusing. However, for Harry, there is content in the very form of surveillance. The secret is, for him, what one might call, an imaginary phallus: the embodiment of an impossible intimacy; and he reacts to Bernie’s prank as if he’s been castrated by him, angrily snapping Bernie’s pen microphone in two. Harry doesn’t exchange secrets with his lovers and friends because, for him, secrets are not exchangeable. They are either guarded or stolen. Harry fails – or even refuses – to appreciate that secrets are valuable only in so far as they are exchanged. So, he finds himself engaged in a battle, either trying to steal the secrets of others or trying to guard his own; and his inability to converse correlates directly with his investment in the conversation.

- The Call / Caul of the Other

If we thus understand Harry’s professional eavesdropping not as merely instrumental, but rather as informed and sustained by the surplus-enjoyment of sexual rivalry, then his anxious guilt about the possibility that his work might contribute to violence against the young couple appears to be due not to the fact that his merely instrumental reasoning has blinded him to considerations of the ultimate value of his actions. Instead, it seems, some such violence too closely approximates the value that implicitly motivates and sustains his work, which the pretense to “just doing his job” enables him to disavow.

The focus of Harry’s interest in the particular case is the adulterous young wife, who seems simultaneously to mean several different things to him. On the one hand, he expresses romantic interest in her, when he compares her to his girlfriend Amy. On the other hand, she seems to bear maternal significance for him, as he repeatedly plays the segment of the taped conversation in which she expresses motherly concern for a derelict, passed out on a park bench.

[Everytime I see one of those old guys, I think the same thing… I always think that he was once somebody’s baby boy… and he had a mother and a father who loved him; and now there he is half-dead on a park bench, and where are his mother and father and all his uncles now.]How Harry positions himself in relationship to her in the act of surveillance is similarly complex and perhaps could be elaborated in as many diverse combinations as I spelled out above in my exposition of The Moran S15 Harmonica Tap. That is, as a jealous lover, a rebellious child, a punitive father. Most importantly, he seems to maintain conflicting attitudes towards her; and the dynamics of the conflicts in his relationship to her change as the film unfolds.

Initially, we might venture he occupies the position of a punitive father and husband. Precisely because this is the violence he fears, the enjoyment he derives from his eavesdropping would seem to be the sadistic gratification of the super-ego, reaping his revenge on the adulterous (or even incestuous) couple. However, if the sadistic enjoyment of the super-ego initially seems predominant in Harry’s anxious guilt, it cannot be divorced from the fantasy of simultaneously occupying the position of the incestuous son, stealing forbidden intimacies and provoking the angry father’s rage. His violence is leveled against those who would enjoy that which he is not allowed, as well as against himself, in his self-reproaches; and, as the film unfolds, the emphasis in Harry’s investment in the case shifts in this direction. He assumes the role of the incestuous son, defending the young adulterous wife, from the paternal rage; while, of course, he still remains invested in that same super-ego enjoyment.

In case these conflicting roles seem all too easily recognizable – as psychoanalytic clichés based upon imaginary identifications – it is important to remember that they are not fundamental in The Conversation but rather present attempts to make sense of a demand – or, one might say, a call – that Harry does not understand but feels compelled to address. On the tapes this compelling demand is concentrated in a clip that Harry finds particularly exciting and distressing. Immediately following his disagreement with Bernie, he’s alone with Meredith in his warehouse and, in his upset, stands at his desk and plays the tape, despite the fact that Meredith is trying to seduce him. “She sounds frightened,” he mumbles, “Its no ordinary conversation. It makes me feel something…” Then, as Meredith begins to kiss him, he flinches reflexively disturbed, when the young wife on the tape, whines, “Oh God.”

“Oh God,” he says, “listen to the way she says, ‘Oh God.”

The phrase includes maternal love as an expression of concern, sexual desire as an ecstatic moan, and religious devotion as a plea. Harry circulates between these various misunderstandings, not as confused alternatives, but as conflicting demands that he can neither reconcile nor abandon. The call he answers – C-A-L-L – lays claim to him with the overwhelming embrace of a Caul – C-A-U-L – the translucent embryonic sac that sometimes remains attached to newborns. And in his anxious response, the two are echoed, as mutually reinforcing and complimentary imagos of maternal longing and paternal rage, which – as fully realized in the film’s closing scene – hold Harry trapped.

[1] UNNECESSARY NOW: In a 1982 interview about The Convervsation, titled “‘America’s Culture Is Controlled by Cynical Middlemen,” Coppola provided further support for this reading of the film by arguing X, Y, Z