Un/Freedom: Civilization’s Discontent and the Traversal of Fantasy

These reflections were presented at an Annual Meeting of the LACK: Society for Lacanian Psychoanalysis at Colorado College. They can be cited here as: Buckner, Clark. Un/Freedom: Civilization’s Discontent and the Traversal of Fantasy. www.clarkbuckner.com. Web. Day, Month, Year article as accessed.

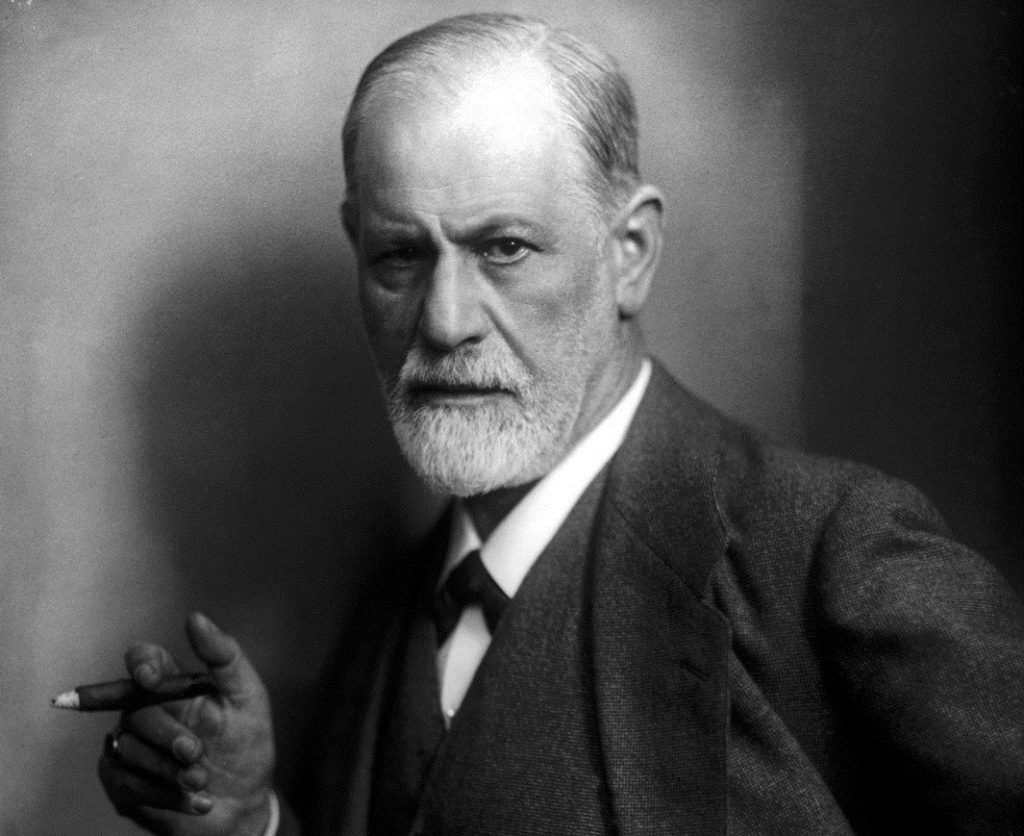

In the Fall of 1909, as Freud arrived for the first time on the shores of the United States – on his way to deliver a lecture at Clark University on the new science of psychoanalysis – he famously turned to his traveling companions and remarked, “They don’t realize that we bring them the plague.” At first glance, this sickness in psychoanalysis might simply be understood in terms of the seemingly corrupting importance that it attributes to sex in the psyche. Yet, if it is to carry any weight today, the scandal of psychoanalysis has to be conceived as more than just a prurient subversion of prudish Victorian mores. At its core, psychoanalysis presents a decisive challenge to the principle of rational self-determination that is not merely a hallmark of 19th-century positivism but a defining modern value. As Freud came to see it, through his confrontation with neurotics, the autonomous subject develops through a complex of conflicts that both contribute to and contravene its proper functioning. Rather than spontaneously self-determining, he sees the subject as stifled by fixations born of its own conflicted desires. In fact, he conceives the very sense of autonomy as both an expression and a denial of these originary conflicts. And, in this regard, the psychoanalytic plague, which Freud and his colleagues brought to America’s shores, is perhaps best understood as its revelation of humankind’s constitutive unfreedom.

At the same time, however, Freud’s recognition of the fixations integral to character formation was part and parcel of his developing a means to loosen their hold on his patients’ psyches. While challenging the assumption of autonomy as either immediately given or an ultimately achievable end, Freud does not therefore dismiss it altogether. Instead, he develops an expanded, second-order theory of self-determination, one in which the subject is conceived as affectively conflicted, integrally bound up with others, and calling for continuous re-consideration. Despite the scandal of psychoanalysis, Freud accordingly provides support for conceiving analysis as an emancipatory discourse, aligning it, for example in The Future of an Illusion, with the enlightenment project of remaking the world in the light of reason. [Quote/More] However, in Civilization and its Discontents, Freud casts deeper suspicion on this project and, in the process, problematizes the normative aim of his psychoanalytic method. [Quote/More]

So the question remains, is psychoanalysis a liberating discourse? Does it champion or aspire to freedom as an orienting value? And how, specifically, are these questions addressed in Lacan’s critical theory?

In this presentation, I want to sketch an intial approach to these questions by expositing the problem of unconscious guilt at the core of Freud’s concept of civilization’s discontent and tracing Lacan’s correlative turn against the idealistic implications of his own earlier work: first, through the critical revision of his drive theory, and, then, through his elaboration of its implications for his concept of the law. In so doing, I propose to clarify Lacan’s similarly pessimistic conclusions about civilization, and to reflect on how his concept of the subject’s constitutive un/freedom problematizes the question concerning the ethics of psychoanalysis.

The Unconscious Sense of Guilt

When first introducing the concept, Freud equates the superego simply with the moral conscience installed in the psyche with the dissolution of the Oedipus complex. As the basis for his pessimistic conclusions in Civilization and its Discontents, however, he subsequently argues that the superego is distinguished from the moral law by the unrelenting insistence that renders it self-contradictory. Whereas the law’s mediation of ethical conflicts serves a pacifying function, as Freud explains it, conceding the superego’s demands only fuels their stricter prosecution. Despite the normative content of its injunctions, the superego exerts an unjustifiably cruel fury that paradoxically compromises the integrity of its principles and so, as Slavoj Zizek emphasizes, qualifies it as essentially transgressive.

While liberating society from the strictures of tradition, the repudiation of the Sovereign Good, traditionally attributed to the Father, paradoxically brought to light the inherently contradictory nature of law. As distilled most rigorously in Kant’s moral philosophy, the law’s justification appeared to be strictly self-referential, as if to say, “The law is the law!” While Kant conceives this self-reference as the essence of the subject’s moral autonomy, in the absence of metaphysical basis the authority of law betrays an insistence that cannot be justified on strictly rational grounds. Subsequent thinkers both register this contradiction and attempt to account for its motivating force. Most famously, Karl Marx argues that the law’s groundless formalism disavows the class-conflict that informs its institution. Nietzsche explains the excessive, strife-laden force in law as will-to-power. And Freud conceives it as the compulsion of drive-conflict, which sustains the ideology of the Sovereign Good in the paternal imagos of the unconscious (Santner, 1996; 9–16).

In this regard, Freud’s celebrated account of religion as “the universal obsessional neurosis of humanity” is perhaps better understood in reverse (Freud, 1957; 21: 43). While the thrust of Freud’s assertion undoubtedly lies in his critique of religious practice as the collective sublimation of unconscious conflict, Freud simultaneously situates the emergence of neurotic suffering in relationship to the breakdown of traditional social institutions and the secularization of the modern world. So understood, the accomplishment of Enlightenment self-consciousness has been coupled with the unconscious persistence of the paternal figures that informed traditional religious and social institutions, while simultaneously intensifying the affective conflicts that sustained them in light of the ultimate groundlessness of publicly sanctioned authorities. As the converse of Freud’s critique of religion as a collective neurosis, that is, obsessional neurotics perform symbolic rituals, which redress the strife in their experience through their “own private” religious passions.

Accordingly, the crisis that existentialist philosophers address as the problem “nihilism” reveals itself to Freud in his patients’ symptoms, well before he explicitly turns his attention to the discontent in civilization and, in his teaching, Lacan explicitly elaborates this connection. However, Lacan also contests the existentialist formulation of the problem it presents, at least in the Nietzschean proclamation of God’s death. In his 1964 Seminar, Lacan argues, “The true formula of atheism is not God is dead,” but rather, “God is unconscious” (Lacan, 1998; 59). And as early as his 1954-1955 Seminar, Lacan contests Dostoyevsky’s postulate—put forth by a panicked priest in The Brothers Karamazov—that, if God doesn’t exist, then everything is permitted. “Quite evidently a naïve notion,” Lacan retorts, “for we analysts know full well that if God doesn’t exist, then nothing at all is permitted any longer. Neurotics prove that to us every day” (Lacan, 1991; 128). While Dostoyevsky’s priest supposes that God’s death leaves a void, sanctioning anarchic depravity, neurotic suffering reveals that the sense of guilt is not merely a result of the authoritarianism of religious institutions, but rather symptomatic of the affective conflicts in subjectivity and social life that first informed their establishment. Despite his virulent atheism, in Civilization and Its Discontents Freud accordingly applauds traditional religious institutions for at least having provided means to mitigate these conflicts, and he argues that the paradoxical price of civilization’s advance is “a loss of happiness through the heightening of the sense of guilt” (Freud, 1957; 21: 134). Instead of relieving the sense of guilt, the repudiation of God’s transcendence rendered it amorphous as an inchoate anxiety that lacks solid grounds, or even determinate limits, and so pervades experience. Rather than permitting everything, the death of God accordingly seizes the modern subject in a psychical paralysis, which the unconscious persistence of religious illusions both manifests and serves to mitigate. And, as strictly correlative to these unconscious conflicts, the heightened sense of guilt also accounts for the distinct propensity in modernity to devolve into barbarism, as an expression of and an antidote to the unrelenting insistence of the superego’s cruelty.

The Corporeal Insistence of the Drive’s Circuit

Among other ways, in his teaching, Lacan registers this radicalization of the scandal of psychoanalysis, when reformulating his concept of drive. During the 1950’s, Lacan conceived drive in terms of the negativity of the symbolic phallus, and the relentless insistence of the signifying chain, which defines the unconscious as the dis course of the Other. So doing, Lacan accounts for the radical variability of human sexuality. He accounts for the paradigmatic erogenous zones as sites of the signifier’s cut, registered in the phenomenology of the body. And he accounts for the dualism that Freud saw necessary to account for unconscious conflict, by conceiving desire as intrinsically divided between the differential negativity of the symbolic, and the objectivist identification of the imaginary. As the crux of what he later criticizes as the idealism of his own work, however, Lacan’s reformulation of Freud’s drive theory in terms of the primacy of the signifier suffers from a “confusion between the drive and desire” (Miller, 1996b; 422).

In his exposition of this “confusion,” Jacques-Alain Miller takes issue with Lacan’s exhaustive integration of “the drive into the schema of communication.” Echoing the central thesis of Lacan’s “structuralist period,” he protests, “the drive is completely constructed like an unconscious message” (Miller, 1997; 26) Attributing the negativity of the death-drive to the sundering of the symbolic, Lacan equates it with the lack of desire, while he explains drive-conflict (in fact, drive itself) as an effect of the derivative reduction of desire to demand. Correlative to his dissolution of the objectivity of the lost object in the formal negativity of the signifier, Lacan thus dispels the force of the drive, as a compulsive excitation, which chronically disturbs the subject’s self-possessed intentions. While justifiably refusing the objectivist reduction of Freud’s concept to a quasi-biological theory of need, defined by the causal necessity of mechanical determinism, he falls prey to the contrary error of idealistically “elevating” it to a purely symbolic theory of want (or lack) and so – despite the heteronomous dialectic of its constitution – conceiving it essentially as a form of intentionality, or even, freedom.

Against the idealism of his own earlier theory, in the 1960’s, Lacan accordingly revises his concept of drive, insisting first and foremost on its material force: as the efficacy of the Real, which, rather than opening the field of possibility, imposes itself – as the involution of an ontological closure – with an unrelenting, corporeal necessity.

Specifically, in his 1964 Seminar, Lacan insists that “the reality of the unconscious is sexual reality;” and he explains the force of the drive as an effect of the subject’s originary relationship to, neither the lack of desire, nor its derivative reduction to demand, but rather to the real of the lost object (a), registered as jouissance (Lacan, 1998; 150). Contrary to his earlier, exhaustive reduction of the unconscious to the “treasure-trove” of signifiers, Lacan thus conceives the subject as essentially corporeal. However, he does not therefore reduce to the drive to a quasi-naturalistic theory of instinct. As distinct from the rhythmic gratification of instinctual needs, the pressure of the drive is constant: the chronic disturbance of a relentless excitation. In keeping with his account of the object (a), as the remainder of a cut in the Real, prior to the sundering of the signifier, the force of the drive registers the subject’s division from the immediately given, natural world, at the level of its natural physiology. While not yet delimited by the symbolic prohibition, which opens the field of desire, nevertheless the drives exceed the closed circuit of the instincts and the innate rhythm of their satisfaction. They are, as Zizek contends, “already ‘derailed nature’” (Zizek, 2005; 192).

In this regard, when locating the drive’s source in the body, Lacan implicitly conceives the body itself, as neither merely biological, nor merely phenomenological (i.e., symbolic), but rather, somewhere between the two – in fact, one might hypothesize, at the point of their irreducible mutual implication – as a field of compulsive excitations, constituted in its ultimate (in)coherence, by the ‘extimate,’ lost object (a). [OUT][i] As conspicuous, for instance, in the clinical and cultural phenomena of over-eating, the drive does is not sated by the objects on which it is brought to bear, but rather always demands more, another. At the point where over-eating meets anorexia, the object of the drive lies rather in the absence of the remainder: its satisfaction is correlative with its dissatisfaction, as the enjoyment of the craving.

While repudiating his earlier assertion of the primacy of the signifier’s lack, Lacan thus conceives drive itself as the efficacy of an originary negativity. Rooted in the rims of the body’s orifices, the drive relentlessly circumnavigates a categorically lost object, accomplishing nothing. Contrary to his earlier theory, however, Lacan does not conceive the absence of the drive privatively, but rather as the imposing presence of a visceral excitation, whose “lack of lack,” renders it impossible to directly determine; and, rather than the seat of potentiality – as the underdetermination of a want – he conceives its disturbing force as a necessity more insistent than empirical determination.

Superego Overdrive

Famously, in his initial elaboration of the normative implications of the drive – as the coercive force of the Real in the superego’s support for and subversion of the law – Lacan uncannily equates Kant with Sade. Along with repudiating any appeal to the Sovereign Good, in the formulation of his ethics Kant furthermore discounts the moral value of utilitarian considerations of personal advantage and the collective welfare. Instead, Kant approaches the problem of ethics through an analysis of the transcendental conditions of the sense of duty, and he formulates his moral philosophy, in strictly formal terms, by arguing that moral acts are those performed out of respect for the law. For Kant, morality thus concerns the integrity of intentions, and the exercise of autonomy: giving the rule to practical life, independently from such heteronomous considerations.

Specifically, as the fulcrum of his moral philosophy, Kant distills the integrity of the will’s autonomy into an ethical principle in the formulation of his celebrated concept of the categorical imperative. He writes, “Act only according to that maxim whereby you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law” (Kant, 1993; 30). At first glance, Kant’s appeal to the universal might seem to compel the subordination of personal interests to the considerations of the common good. To the contrary, however, Kant argues that such considerations do not account sufficiently, or even necessarily, for the distinctly moral sense of obligation, as transcendent of time and place. In fact, their pursuit might just as well be motivated by sentimental over-identification, vain self-gratification, or any number of other amoral, or even immoral reason. By contrast, the thrust of Kant’s concept lies in the standard of internal consistency that it provides, precisely by purging ones motives of all heteronomous inclination, whether individual or collective. By formulating the maxim of one’s action as a universal law, one dispels from it the particularities that constitute one as an empirical subject – suspending considerations of both personal advantage and historical context – as a radical expression of the rational capacity for principled action.

In this disregard for the subject’s well-being, Lacan recognizes that Kant’s concept of the moral law contravenes the homeostatic regulation of the pleasure-principle, evidencing an implicit cruelty, which is not compensated by the conciliatory promise of a greater good, but rather affirmed as an end-itself. In fact, despite his refusal of any sensuous basis for moral judgments, Kant effectively admits this sadistic dimension of his ethics. He writes, “Consequently, we can see a priori that the moral law as the determining principle of will, by reason of the fact that it sets itself against our inclinations must produce a feeling that one could call pain” (Cited in Lacan, 1992; 80). At the same time, Lacan reads Sade paradoxically as a moralist, not only because, in his life and literature, he pursues his libertinism as a point of principle, but also because the torturers, whom he depicts – the hangmen and executioners – exert their cruelty as a “duty” in the service of a master, without regard for – or even, at times, explicitly contrary to – their own satisfaction. Lacan’s identification of Kant with Sade is not therefore ironic: as if to reveal the hypocritical hedonism of the stern ethicist, while celebrating the indulgent libertine as a paradigm of virtue. Despite the unavoidable humor of his insight, Lacan equates the two sincerely, on the basis of their common articulation of the jouissance – as pleasure-in-pain – that qualifies the moral law, precisely in its formal abstraction.

Along with discerning the sadistic cruelty in the sense of duty, as a second variation on his concept of the super-ego, Lacan argues that the inconsistency in the symbolic “no” of the law manifests itself in the “extra-legal” social codes, which both contravene its explicit principles and provide a necessary supplement to sustain the cohesion of the social body. Before and beyond the letter of the law, that is, social institutions are sustained through a collective indulgence in unspeakable enjoyments, which indeed constitute the subject as constitutively guilty: diabolical, in fact.

As the final variation on his concept of the superego, Lacan accordingly explains it simply as the mandate to “enjoy!” While enjoyment often is affirmed as antithetical to the law – the liberating escape of a primitive, spontaneous satisfaction – precisely in this way, Lacan conceives it as supplementing the symbolic authority of the law. Most conspicuously, the coercive force of enjoyment lies in its refusal of the dissatisfaction that accompanies the law’s restrictions. The imperative to enjoy might therefore be heard as reinforcing the law’s authority, by censoring any of the residual dissent that it inevitably engenders. However, Lacan’s contention is stronger still. The imperative to enjoy itself entails a social coercion, which the law serves to mitigate: it is the demand to be the object of the Other’s satisfaction, which threatens to overwhelm the subject in the vertigo of its solicitation. [TRAVERSING / OUT][ii]

Beyond the Ethics of Castration

While radicalizing his concept of the ethical impasse presented by the dialectic of enlightenment, however, Lacan also problematizes his own concept of the ethics of psychoanalysis. In his work of the 1950’s, of course, Lacan conceived these dialectics in terms of the sundering of the symbolic. While instituting and sustaining the metonymy of desire, this originary negativity simultaneously engenders the propensity to obfuscate its own constitutive lack in the demand for something actual. At the same time, as the basis for his theory of neuroses, these dialectics thus account for the ethics of psychoanalysis: as matter of resolving such reifying fixations through the symbolic work of interpretation and more challenging the analysand to more fully realize his or her desire by assuming the lack of castration.

As Lacan comes to conceive it, however, the symbolic order of language and society is not delimited by the pure lack of a differential principle, whose formal negativity holds open the always outstanding promise of the possible. Instead, as a qualifying conditions of its organizing principles, the Other exploits the subject for its own enjoyment, reaching into its ‘skin’ as a parasite that it will never be able to purge.

Compelling the subject to assume the lack of castration disavows this still more problematic strife in the Real, instituting the deferral of desire as a tireless and ultimately self-defeating circuit of prohibition and transgression. As Joan Copjec explains it, “The more we define ourselves as mere becoming, the more we place ourselves in the service of a cruel and punishing service of a cruel and punishing law of sacrifice, or, as Lacan says, a ‘dark God’” (Copjec, 2004; 151)

At the same time, it bears noting, Lacan’s revision of his critical theory precludes the all-too-common reduction of his concept of the normativity of analysis to the deconstructionist ethics of alterity. Rather than the problem of unconscious guilt, in fact, Derrida conceives the ethical impasse presented by the dialectic of enlightenment in terms of the problem of good conscience. As he contends in the essay, “Force of Law,” for instance, the symbolic sundering of the law remains unavoidably qualified by the imaginary reification of identity in the concrete conditions of its articulation; and this undecidability in its structure and genesis both requires and makes possible its deconstruction. While redoubling the dialectics of identity and difference, in his critical theory, Derrida thus preserves the purely formal concept of negativity, which Lacan repudiates in his own earlier thought. As evident, for instance, in his concept of the efficacy of difference, he purges the psychoanalytic concept of the irrational of its material insistence, as a overwhelming corporeal excitation, which imposes itself with an unrelenting necessity; and, on this basis, finds grounds for addressing the impasse it presents, by holding open the promise of the Other in its radical alterity. Indeed, because Derrida disavows the jouissance of the drive in his concept of the extra-legal conditions of the law, his concept of deconstruction’s normativity evidences the same sadistic coercion that Lacan discerns in Kant’s moral philosophy and, implicitly, his own earlier theory. For, what is his insistence on the virtue of deferentially acquiescing to the Other, except a variation on the injunction: Enjoy!

[i] While locating the source of the drive in the body, Lacan thus simultaneously distinguishes the object of the drive from the object of instinctual need. Whereas instincts entail a determinate relationship to their object, Lacan argues that the drive has no objective correlative. Citing Freud, he contends, “Look what he says, ‘As far as the object of the drive is concerned, let it be clear that it is, strictly speaking, of no importance. It is a matter of total indifference’ (Lacan, 1998; 168). The object of the drive is, according to Lacan, the Real of the lost object. Despite the force of its claim on the subject’s body, strictly speaking, it thus amounts only to “a hollow, a void,” for which objects of instinctual gratification (among others) only secondarily serve as surrogates (Lacan, 1978; 180). Lacan contends, “No food will ever satisfy the oral drive, except by circumventing the eternally lacking object” (Lacan, 1978; 180).

Bringing together the “void” of the drive’s object with the “rim” of its source, Lacan depicts the force of the drive in a vivid image. “Even when you stuff the mouth – the mouth that opens in the register of the drive –“ he contends, “it is not the food that satisfies it, it is, as one says, the pleasure of the mouth” (Lacan, 1978; 167 – 168).

[ii] Traversing the Fantasy: While radicalizing his account of the ethical impasse presented by the dialectic of enlightenment, Lacan’s revision of his drive theory problematizes his account of the ethics of psychoanalysis. Specifically, the force of this this Real in the law marks a limit to interpretation, requiring a critical confrontation with the jouissance in the symbolic, independently from the meaning or meaninglessness of symptoms. Lacan accordingly rethinks the critical normativity in psychoanalysis as an ethics of the drive, in terms of, what he calls, traversing the fantasy. In the closing session of his 1964 Seminar, Lacan asks, “How can a subject who has traversed the radical fantasy experience the drive?” (Lacan, 1998; 273). While he only uses the phrase this once, the concept of traversing the fantasy has gained widespread usage as a general term for the diverse approaches that Lacan develops, in his later thinking, when addressing the ends of psychoanalysis in relationship to the jouissance of the drive. Among other ways, in his exposition of Lacan’s concept, Žižek appeals to Freud’s distinction between the interpretation of symptoms and the construction of the fantasy. In light of his original appeal to structural linguistics, Lacan conceives fantasy as misconstruing the symbolic lack of desire in the demand for something actual and, on this basis, assumes the interpretation of symptoms to hold the promise of the fantasy’s dissolution in the assumption of castration. In his theory of sublimation, Lacan contends that the mediation of imaginary particulars plays a generative role in articulating the organizing principles of the symbolic, but he still explains the two, symptom and fantasy, as essentially coextensive in their symbolic delimitation. In light of Lacan’s postulate of a cut in the Real before and beyond the sundering of the symbolic, however, he conceives the institution of the fantasy frame as prior to and independent from the lack of its organizing principles. Of course, interpreting symptoms still plays an important role in clinical practice, restoring the dialectical flexibility in the analysand’s desire by lessening its fixations and decreasing their motivating anxiety. However, addressing the analysand’s conflicts ultimately requires the analyst to speculatively reconstruct the fantasy that institutes and sustains the subject’s relationship to the Other.

While symptoms presuppose the symbolic order that retroactively renders them meaningful, the fundamental fantasy stages the gratification that institutes and sustains the authority of the Other in the Real that renders it incoherent. Whereas desire is “on the side of the Other,” Lacan contends, “Jouissance is on the side of the Thing” (Lacan, 2006; 853/724). Accordingly, the interpretation of symptoms and the construction of the fantasy are not only independent of one another but entail contrary affective dynamics. While symptoms disturbingly subvert one’s sense of self-possession, their interpretation tends to be pleasurable as an intersubjective articulation of unconscious desire. By contrast, the private reveries of fantasy are terrifically pleasurable. However, their disclosure tends to cause discomfort and shame (Žižek, 1989; 74). Strictly understood, in fact, traversing the fantasy necessarily entails this disturbing affect. As a critical practice, its force lies in refusing the distance that enables the subject to disavow the gratification in its symbolic articulation of experience. Contrary to the post-phenomenological insistence on the undecidable, Lacan conceives skeptical reflection as essential to upholding rather than subverting the symbolic. What causes the symbolic to collapse is rather the all too immediate realization of the gratification that institutes and sustains its organizing principles. Accordingly, traversing the fantasy compels this confrontation, bringing the subject to the point where the fantasy frame proves impossible to sustain in light of the unbearable proximity of its enjoyment.